Working in a Department Store

It wasn’t that bad. My father often tells me about his father’s job as a steeplejack: that sounds bad. At least I was indoors and not teetering hundreds of feet above the cold, hard ground.

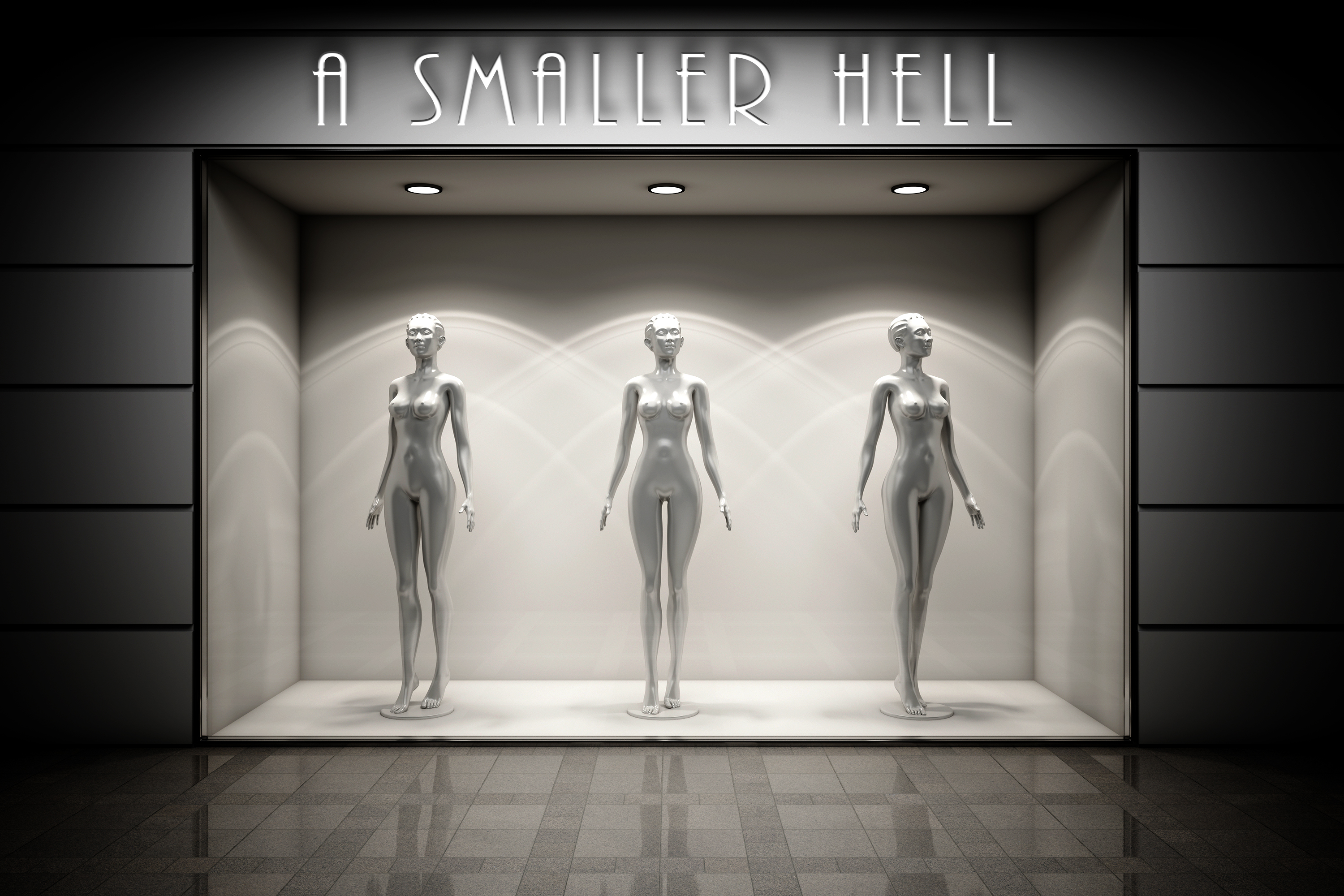

At the interview, I didn’t have a panic attack and smash up a waiting room as Tony Black does in A Smaller Hell. Instead, I was sneered at by a snotty manager for ten minutes before she found out where I went to school and then it was all la-de-da-do-you-know-so-and-so. I knew a few people and suddenly I was the perfect candidate. Never once did she mention the exam grades I had sweated over, or the money I’d raised for charity, or my love of Satie, just the fact that it was lovely to have another Old Birkonian on board. Jolly good show.

I was being welcomed into the inner sanctum of an institution. The lethal polished floors and automatic doors; the toy guns; the sparkling jewellery displays; the luxurious waft of the perfume counters; the smell of the posh Rombout’s coffee and Welsh Rarebit in the cafe. I was usually accompanied by my nan, who would take me there on the bus while my parents were at work.

At 6 years old, the Toy department was sacred ground, scented with erasers, bubblegum and gunpowder from the caps for the toy guns. With the acquisition of a new toy, adventure inevitably followed. At 10 years old, I became obsessed with writing equipment, and would often be shooed away from peering into the glowing glass cabinets. By 16, I was Christmas shopping there with my first girlfriend. We wore scarves and puffer jackets, and I remember her fingers feeling skinny even through her rainbow-coloured wool gloves. She had long black hair, pale skin and green eyes. Her fine cheekbones were always rouged by the cold weather and she shivered a lot in her rusty Nissan Micra with no heater, which made her look fragile and beautiful.

And so at 24, I found myself working in this castle of memories. And like every good castle, it had a hierarchy within its walls – and like every good hierarchy, it had its tyrants, climbers and victims. It was very much like returning to school. Every morning, I would feel the polyester of my tie catch on the callouses of my left hand’s fingertips: a stark reminder that the dizzying heights of yesteryear – with its six-figure record deal offers, hotel rooms in Manhattan, yachts in Marina Del Rey, famous rock lawyers and all the rest of it – were long gone. Every morning was soundtracked by a lonely drizzle and painted entirely in grey.

Nevertheless, every day, I tightened my polyester noose and bought my bus ticket. Every day, The George and Dragon’s warm wafts of stale ale would greet me on the way in and out of work. Every day, I would get told off for being late back in from my lunch break, even though it would be a matter of seconds. Every day, I would fantasise about windmilling through the China and Crystal departments like someone on day release, just to see the look on my boss’ face.

Every day.